Episode 12: I GOT SHOT FOR THIS

[SHOOTING]

I liked the idea of shooting someone… for art

— Bruce Dunlap

[BURDEN]

A fuzzy, blurry 4:3 video fills the screen.

Not quite fills the screen.

This is a modern 16:9 monitor. There are black bars at either side to accommodate the footage of back then.

Two indistinct humanoid figures occupy the space. They both seem to be wearing dark trousers and white tops, but other details are hard to distinguish.

They appear ghostly, but not in a transparent way. They appear ghostly in an indefinable sense. Vague. They could be anyone.

One thing is clear, however. The figure on the right is pointing a gun at the figure, fifteen feet away, on the left. It looks like some sort of rifle.

There is the echoing bang of an indoor gunshot.

The figure on the left clutches their left arm.

They clutch it mid-way between the elbow and the shoulder.

The camera centres on them, clipping out the figure on the right.

The shot figure staggers forward on unbending legs, inspecting their own arm.

They lift the cuff of their t-shirt and peer beneath.

We see no blood. We see no damage.

The wounded figure exits to the right of the frame.

[GUNS]

Japan has a long history of gun control.

Firearms were first introduced to the country during the first Mongol invasion of the 13th century in what was probably the first example of gunpowder-based warfare outside of China. These weapons were closer to flash-bangs and grenades, although there were early prototypes of hand cannons called ‘teppō’.

The Portuguese brought more modern guns to the party in 1543.

The feudal lord, Tanegashima Tokitaka, who the gun would later be named after, purchased two of these weapons and tasked his blacksmiths — former sword-makers — with creating replicas.

In just a few years, warfare in Japan was radically changed with the tanegashima steadily replacing the traditional sword combat.

War at a distance.

War with a bang.

A warlord in Japan, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, attempted to control weapons in 1588, as a way of suppressing a peasant revolt. He confiscated weapons as part of a ‘sword hunt’. Guns were similarly collected, with the intention of melting them down to create a giant statue of Buddha.

This did little to stem the tide, and the early Portuguese models were supplemented with British, American and Spanish firearms.

The Japanese also developed their own weapons, with notable inclusions being the Nambu, a recoil operated, locked breech, semi-automatic pistol that looks so like it has fallen out of a science fiction film.

It looks so like a laser pistol that a modified version was used in the Star Wars show, The Mandalorian.

After World War Two, stricter rules for gun ownership were brought in. The Japanese military was disarmed, another Sword Hunt was instigated in 1946 leading to over three million swords being confiscated.

The government then enacted the Swords and Firearms Possession Control Law in 1958.

As such, gun ownership in Japan is rather limited. The police do have guns under lock at police stations but rarely deploy them. Police officers themselves tend to train in kendo and judo rather than small arms.

Shooting sports are similarly tightly controlled. Paintball, for example, is far less popular than many countries.

There is a sense that firearms are the tools of the oppressor, not the oppressed.

However, it would be Japan that would bring in the Airsoft revolution of the 1980s.

[WESTERNS]

Cowboys were neat.

Cowboys were pretty cool.

They were the Marvel superheroes of their day.

Gun-toting, law-dispensing Cow-Man, and his sidekick, horse-horse.

To say that Hollywood was saturated with Westerns is perhaps an overstatement, but there were an awful lot of them.

It is estimated that, between 1940 and 1960, 140 Westerns were made each year in the US.

If we take Spaghetti Westerns into account, we can add another 500 or so up until the late 70s.

That means there are certainly over 3,000 of them.

There are many theories as to why this may be. A re-imagining of America’s Manifest Destiny. A return to stories from a simpler time where it was easier to work out who the bad guys were. Cheap, abundant sets and workforces. The sort of Ouroboros of advertising creating a demand and satisfying that demand in a demented whirlwind.

I meant to ask, do you know who Tom Mix is?

He was incredibly famous.

Famous and prolific.

It is thought that he is the actor to appear in the most Westerns.

Between 1913 and 1917, whilst under contract with Selig, Mix made 171 films.

Then, from 1918 to 1928 he would go on to make 86 films for Fox.

Things slowed down to a glacial pace between 1928 and 1929 where he made just five films in a year for the Film Booking Offices of America (FBO).

A short break was followed by the period between 1932 and 1933 where he picked up speed again and made 10 films for Universal.

His final film, the only one he would make for Mascot, came in 1935.

273 films.

In 22 years.

That’s one a month for two decades.

And all of this before the genre hit its peak.

[GUNS]

In the early 1970s a Japanese photography enthusiast and fan of Western films, Ichiro Nagata, thought about making model guns that didn’t do too much damage to the target.

Nagata had been particularly influenced by the American BB guns from Daisy, particularly the spring-air rifles marketed at children during the height of Western mania.

He started with spring-loaded kinetic guns and then progressed to a gas mixture propellant of freon and and silicone oil, known as “soft air”. This gas would later be replaced with a mixture of propane and silicone oil, called “green gas”, but the “soft air” name had stuck.

Plus, the propellant was significantly weaker than the carbon dioxide used in paintball guns, making them legal in Japan despite the strict gun control.

The intention was to use these guns for target shooting, however, it quickly became apparent that you could shoot people with them without causing too much pain.

And so it was that Airsoft was invented. Within a few years it had spread across the globe.

[LANGUAGE]

It isn’t a particularly original observation that the language of guns is also the language of cameras.

Aim.

Trigger.

Shoot.

Susan Sontag in On Photography puts it in context:

“To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them that they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed. Just as a camera is a sublimation of the gun, to photograph someone is a subliminal murder — a soft murder, appropriate to a sad, frightened time.”

This isn’t just a fanciful notion either. The camera is a weapon. It is a tool of propaganda and information. Warfare and photography have an intertwined history.

Reconnaissance from above. From handheld cameras in hot air balloons to A2 cameras aboard the U2 spy plane during the cold war.

The negatives of the A2 are huge.

Nine inches by eighteen inches.

At an altitude of over six miles up, these cameras could capture objects around twenty foot in size.

Capture.

Then there are the hearts and minds images. Embedded photographers with platoons. A purpose to report the news, but more often that not, a way to spin the situation.

Being there is never just observing, no matter how passive the act seems.

Again, Susan Sontag points this out:

“…using a camera is still a form of participation, Although the camera is an observation station, the act of photographing is more than passive observing. Like sexual voyeurism, it is a way of at least tacitly, often explicitly encouraging whatever is going on to keep on happening. To take a picture is to have an interest in things as they are, in the status quo remaining unchanged.”

[SHOOT]

It’s dark out, but the security light from a nearby garage flickers on, illuminating the gravel and damp grass.

About fifteen feet away my nephew is loading a gun.

It is a gas-powered Airsoft pistol, designed to deliver a 6mm-diameter plastic ball bearing to a target at a speed of about 300 feet per second.

That makes me about 0.04 seconds away.

“I’m going to look away”, I say, turning my back on him.

He asks if I want to know when he is about to fire.

I say that it is probably best that I don’t know.

We are here because tomorrow I might get shot by strangers, and I figured that it was probably a good idea to know how it feels beforehand.

I had a stupid idea that I would try out a stint of simulated war photography. My nephew was heading to his local Airsoft range for an afternoon of shooting at his friends and peers, and I suggested that I come along and take pictures.

There’s a pop, not loud, followed by a pinch in my lower back.

It doesn’t hurt so much. It wasn’t exactly pleasant, but it was bearable.

The little plastic sphere had hit me in my own natural defence. The layer of middle-aged fat that hangs out back there with, apparently, the sole purpose of protecting me from my own bad ideas.

We should try again, says the nephew, in a manner that suggests he is enjoying shooting me more than he is letting on.

OK. One more.

Pop.

Nnnng.

Mhmmmmm.

You little…

ahhhh.

Right on the shoulder blade.

It stung like hubris wrapped in misadventure.

It took me a little while to string a coherent sentence together.

“You do this for fun?” I ask him, as my voice came out an octave higher than normal.

“Yeah,” he says, “but most of us wear some sort of body armour”.

[COWBOYS AND SAMURAI]

It would be easy to suggest that Japan’s love of Americana was the result of World War Two, their defeat and the following occupation, but the truth is a little blurry.

A fuzzy, out of focus thing.

Maybe it goes all the way back to when the Portuguese arrived with those flintlocks.

A familiar pattern. Assimilate and adapt.

There’s this notion that Japan is, or was, an insular nation, however, even before the war there were indications to the contrary.

It has been suggested that an earthquake in Kanto in 1923 helped usher in a burgeoning middle class. The rebuilding of urban centres created a modernisation that led to gas and electric being common. It created a small boom, leading to disposable income.

Suddenly people were enjoying imported music and baseball, and hotdogs.

Burgers.

Bourbon.

Leather Jackets.

Comic strips.

Teenagers.

Westerns.

This wasn’t a single sided relationship.

As the Japanese were enjoying the the arrival of Tom Mix’s prolific output, they were also busy making their own films.

Japan has, arguably, one of the oldest traditions of cinema in the world, dating back to the 1910s with the establishment of the film studio, Nikkatsu, which is still producing film and television today.

The earthquake in Kanto also prompted the film studios to modernise too. The new equipment influencing a move away from the more traditional theatre-based productions and towards a more westernised form of film making.

There was a modest market for these Japanese films abroad, mostly art house cinemas and smaller specialist theatres. However, it also exposed the films to a different audience. Film Makers.

A number of Japanese films were unofficially remade (a term that seems far kinder than “stolen”) and the stories seemed to fit rather neatly into the Western format.

Something about the stories of Samurai, their honour system, their exploits, and their weapons appealed to Western film makers.

For example, the 1961 film Yojimbo, made by Akira Kurosawa.

This would appear as the Western, A Fistful of Dollars.

Kurosawa wrote to Sergio Leone, saying, “Signor Leone, I have just had the chance to see your film. It is a very fine film, but it is my film.”

Kurosawa would sue successfully over this and it is thought that Toho, Kurosawa’s production company, made more money from A Fistful of Dollars than it did from Yojimbo.

A more legitimate translation occurred with Kurosawa’s 1954 film, The Seven Samurai, which became The Magnificent Seven. Transplanting the action from Sengoku period Japan to 1879 at the Mexican-American border.

Interestingly, The Seven Samurai seems to itself have been influenced by previous westerns, particularly those made by the Director John Ford.

Kurosawa wasn’t impressed though. He said, "The American copy is a disappointment. Although entertaining, it is not a version of Seven Samurai".

[WESTERNS]

I think one of the reasons why the Westerns became so popular is that the period being depicted also happened to coincide with the arrival of mass photography.

Between the 1860s and the 1900s the world saw the progression of Daguerreotypes to Wet Colloidal to film cameras.

Each advance made photography easier and more portable.

As pioneers made their way across the continent, so did photography colonise the lives of the new pioneers.

Yet, despite these advances, photography was still a slow process. Exposure times were still relatively long and subjects would have to sit posed.

I think it is this factor that helped create the cinematic myth of the Wild West.

First, it meant that photography was very suited to panoramic photographs of landscapes, where the black and white images created moody, brooding sculptures of a new land.

Secondly, there were no action shots. No gun fights, no cattle rustling. Only the ephemera and tales of such things supported by posed photographs of the players involved.

These two things created both the set design and the need to show the action, all framed by these stories of rugged pioneers, freedom and the taming of the wild.

[RULES]

The Geneva Convention is, as far as modern warfare goes, a fairly comprehensive rule book.

Specifically, there’s a section on war and journalists.

Journalists in war zones must be treated as civilians and protected as such, as long as they don't participate in hostilities — Article 79

Journalists should be protected as civilians if they take no action that negatively affects their status as civilians — Additional Protocol I

What this means is, essentially, that you can’t shoot war photographers.

There are some caveats to this. In order to be treated as civilians, war photographers should not be firing guns at the opposing side, because if they do, that would make them combatants. Furthermore, you could argue that even carrying a gun in a war zone creates enough of a distinction between civilian and combatant.

There’s another reason war photographers tend not to carry weapons, and this is a question of ethics. If you carry a weapon, you have picked a side and suddenly you are not reporting on a war, you are creating propaganda.

Interestingly, the current conflict in Gaza between Hamas and Israel highlights some of the problems.

During combat, soldiers in this role are required to assess every situation and be able to determine when to fire their guns and when it is the right time to document the events that are occurring around them on the battlefield.

(The Jerusalem Post, 02/05/2024)

Photographers embedded with the IDF carry guns. In fact, these are not photographers embedded with a unit, they are soldiers that have been given a camera.

The picture is, perhaps, deliberately blurred.

Aside for the notions of impartiality and veracity, there is another problem here.

Imagine you are fighting against a unit, and you follow the Geneva Convention. You see a photographer. You don’t shoot, only for them to raise a sidearm and shoot you.

The camera becomes more than just a weapon of propaganda, it becomes a defence on the battlefield.

[WAIVER]

We are going to need you to sign the waiver.

A side of A4 is slid across the counter with a pen. I read it.

It’s the usual sort of thing. I accept full responsibility to any damage that might occur to me, or my equipment. Furthermore, I will adhere to the rules of combat and adhere to all the safety guidelines.

I sign.

I’m enlisted.

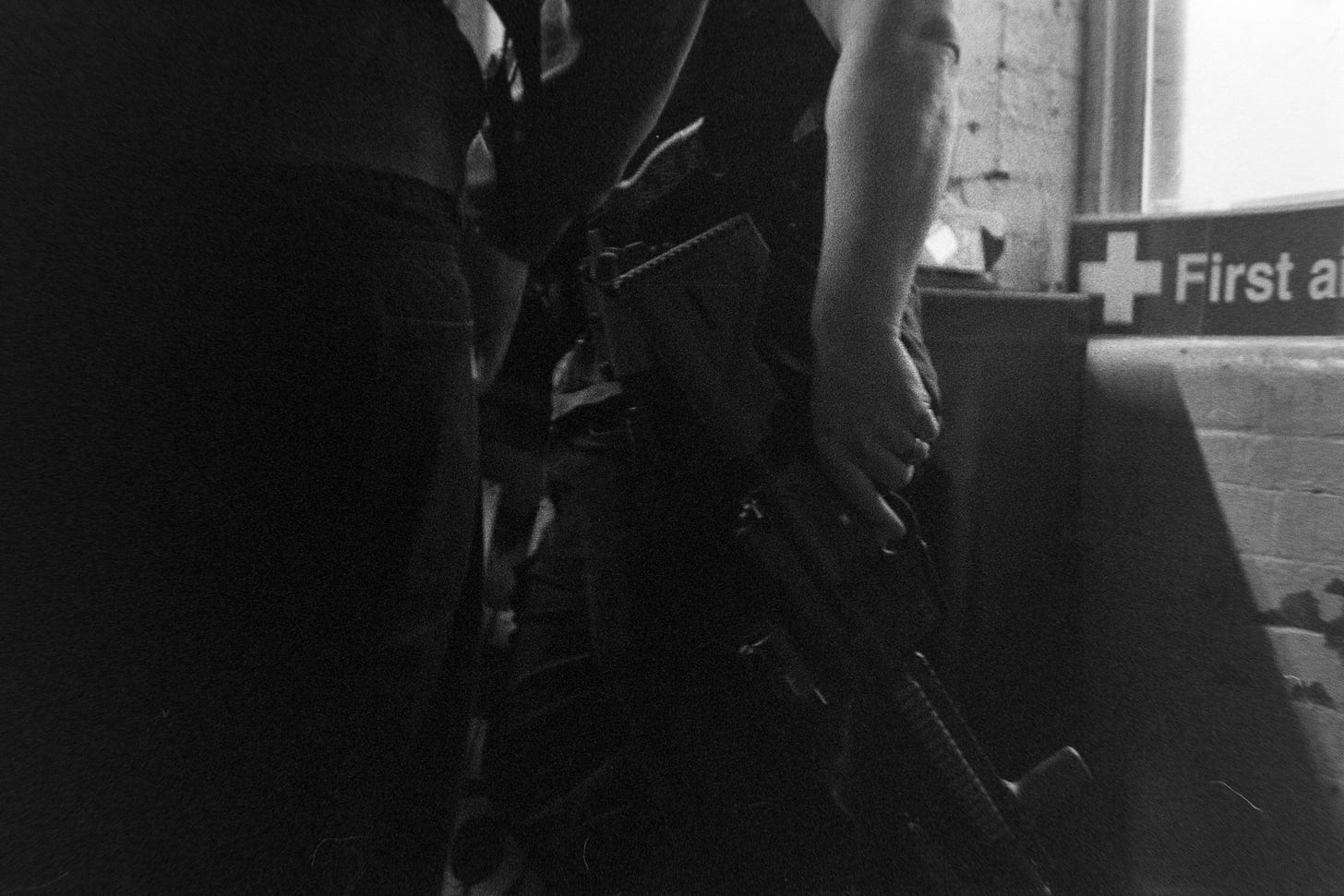

I get handed a hi-vis vest and a pair of goggles.

The goggles don’t fit over my glasses, so I’m now shooting a little blinder than usual. I’ll have to rely on my estimation of distance to focus.

I’m asked if I would like a gun. I decline the offer.

I’m asked again, if I’m sure I wouldn’t like a gun.

I say that the camera is the only thing I intend to shoot with.

I look around and notice that most of the combatants have body armour. Many have full face masks. Several have ear protectors.

I hear that the ear is a terrible place to get shot.

So are the fingers.

My fingers look particularly naked as they cradle the camera.

I recall the pain in my shoulder blade.

OK, they say, time for the briefing.

I head into the warzone.

[WAR PHOTOGRAPHS]

The Spanish Civil War: Robert Capa’s, The Falling Soldier, September, 1936

A soldier is frozen at the moment of his death, collapsing backwards after being shot in the head. He is dressed in civilian clothes, but is wearing a bandoleer.

The rifle rests gently, perpendicular and pointing at the sky, in the hands of the soldier.

Whilst universally recognised as one of the greatest war photographs, the black and white image has been the subject of some controversy since it was first published in Vu magazine.

I was there in the trench with about twenty milicianos ... I just kind of put my camera above my head and even [sic] didn't look and clicked the picture, when they moved over the trench. And that was all. ... [T]hat camera which I hold [sic] above my head just caught a man at the moment when he was shot. That was probably the best picture I ever took. I never saw the picture in the frame because the camera was far above my head.

— Robert Capa

Hiroshima: Yoshito Matsushige’s Photographs, August 6, 1945

On the morning following the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima, Yoshito Matsushige would take the only photographs that would document the immediate aftermath.

In one of the black and white images, taken less than one and a half miles from the epicentre of the blast, police are pouring cooking oil onto the backs of children to soothe their burns. Crowds mill around, surrounded by rubble and debris.

In another image, Matsushige’s wife, wearing an air raid helmet, stands by a sink in the battered remains of their barbershop. Two barber’s chairs seem relatively untouched, whilst the rest of the building appears mostly obliterated. It appears that Matsushige’s wife is trying to tidy up despite the obvious futility.

I had finished breakfast and was getting ready to go to the newspaper when it happened. There was a flash from the indoor wires as if lightning had struck. I didn’t hear any sound, how shall I say, the world around me turned bright white. And I was momentarily blinded as if a magnesium light had lit up in front of my eyes. Immediately after that, the blast came. I was bare from the waist up, and the blast was so intense, it felt like hundreds of needles were stabling me all at once. The blast grew large holes in the walls of the first and second floor. I could barely see the room because of all the dirt. I pulled my camera and the clothes issued by the military headquarters out from under the mound of the debris, and I got dressed.

— Yoshito Matsushige

Matsushige would die at the age of 92 in 2005.

Vietnam: Don McCullin’s, Shell-shocked US Marine, The Battle of Hue, 1968

A marine fills the full frame of the shot. His hands grasp the rifle in front of him which is pointing upwards, seemingly resting on the ground just out of shot, implying that the soldier is sat or crouching.

Beneath the rim of his helmet are two wide eyes, staring straight ahead and strangely unfocused. They set the tone for an expression that is both blank and haunted.

Whilst this is a powerful image in its own right, it is perhaps best combined with McCullin’s entire body of war photography which creates an unflinching and profoundly human study of modern warfare.

It's not important that I record every tragedy that goes on in the world. But I decided to try a couple of shots. And I did something despicable. I wound the car window down and took the photographs from inside. Then I hated myself for not having the decency and courage to at least get out and do something...

— Don McCullin

McCullin later shifted his focus from war photography to landscape photography.

The reason I am doing these new landscapes, this new Roman project, is because it's a form of healing. I'm kind of healing myself. I don't have those bad dreams. But you can never run away from what you've seen.

— Don McCullin

[RULES]

As you would hope, the rules are concise, mandatory and enforced.

I’m very much reassured by how well the place is run. Safety is everything.

Which feels somewhat at odds with the idea that these people are all about to enter into a situation where they shoot at each other.

In brief, if the marshal says stop, you stop.

If you hear the siren, you stop.

If you are shot, you are dead. This operates on an honour system. If you are caught abusing this you are out.

You do not shoot anyone in a hi-vis vest. If you do it is the same as being shot.

No physical combat. No pushing, punching, kissing or anything else you can’t do in a public swimming pool.

Loaded guns are only allowed past a certain checkpoint.

You do not take your protective eyewear off. Not for a second. We’ve all seen that episode of Byker Grove, no one wants that.

[EMBEDDING]

My guide through the zone is one of the marshals.

We are both wearing the vests. He tells me that it is a good idea to announce yourself before walking around corners, in case you surprise a combatant.

He asks if I am using a flash. I suggest that maybe war photographers wouldn’t use one in case it is mistaken for a muzzle flash. I explain that I’m using a high ISO film and I’m going to take my chances.

We walk into the zone and it is a mass of tight, dimly lit corridors made from chip board. There are doorways and random bits of cover. It is an abstract landscape that mimics the frenetic close quarters combat of urban warfare.

“Don’t worry,” he says, “if you stick with me it will be fine.”

I turn around to respond and find he’s already gone.

I’m in the middle of a potential gunfight without a gun. There are two teams now on their way to converge on a point near where I am stood.

It is dim. I am disorientated and somewhat lost.

The battlefield is the size of a large warehouse. I don’t have a map.

Suddenly there is a line of green that whizzes past me.

It’s a tracer round. They actually have them!

I can’t see who fired it.

“Marshal!” I shout, somewhat weakly.

[PHOTOGRAPHER’S CREED]

The following is adapted from the Rifleman’s Creed.

This is my camera. There are many like it, but this one is mine.

My camera is my best friend. It is my life. I must master it as I must master my life.

Without me, my camera is useless. Without my camera, I am useless. I must shoot my camera true. I must shoot straighter than my subject who is trying to kill me. I must shoot him before he shoots me. I will ...

My camera and I know that what counts in war is not the shots we take, the noise of our shutter, nor the film we load. We know that it is the photographs that count. We will photograph ...

My camera is human, even as I [am human], because it is my life. Thus, I will learn it as a brother. I will learn its weaknesses, its strength, its parts, its accessories, its sights and its barrel. I will keep my camera clean and ready, even as I am clean and ready. We will become part of each other. We will ...

[RICOH]

I’m using a compact rangefinder.

It’s a Ricoh 500 RF that I picked up second hand for £20. It needed a little bit of work, particularly new light seals, and a fair bit of cleaning, but it is a wonderful camera.

It’s a reliable camera.

Ricoh began as The Riken research institute of Japan in 1917. They became Rikagaku Kōgyō K.K in 1927.

In 1936 the sensitised photographic paper division became Riken Kankōshi K.K., under the leadership of Ichimura Kiyoshi, who is considered the founder of Ricoh, a name that was adopted from the title of their camera products.

The 500 RF is a camera from the 1980s.

It has an automatic mode, but I prefer to use it fully manual.

It is much smaller than the SLRs I own.

A smaller target.

For this mission I’ve attached a clear glass filter to the front and a hood over the lens. This should stop nearly anything but a head on shot.

Probably.

[REPORT FROM THE FRONT]

I decided to pick a side.

It isn’t that I supported their political aims. I’m not sure that they had political aims. It was just that it seemed safer to only have one team shooting in my direction.

The first skirmish occurred in the middle of the zone. One team seemed held up in an area named “The Laboratory” whilst the other attacked from two sides.

Plastic ball bearings rattled everywhere, making a particular thump as they hit the chipboard panels.

I found myself clinging to the walls. The vest seemed like very little protection as rounds ricochet off the surfaces.

One of the combatants has a shotgun that fires multiple rounds at once. It is a mean looking thing, and is being used to sweep the tight corridors.

A combatant next to me is hit.

A curse followed by a shout, “dead man walking” as they returned to their base.

Steadying myself against an area of low cover, I lift my camera to my face. It’s hard to see through the rangefinder window. I can’t get as close as usual due to the safety glasses. I can’t focus because my own glasses were currently enjoying an afternoon off, back in the safe zone.

I’ve plenty of film, so to hell with it. I start taking pictures.

I’ve listened to a lot of war photographers talking about their craft and the one thing they seem to have in common is that they take a lot of photographs. This is not the time to consider things. It is the time to react. I remember Capa holding his camera above the parapet.

The skirmish breaks. Suddenly, I’m alone again.

I make my way through the corridors.

I can hear gunfire in the distance, but I seem unable to find the source. Perhaps it is moving faster than I am. I’m treading quietly. There is a slight crunch underfoot from the hundreds of tiny white spheres on the floor. Something has happened here, but I missed it.

I come to an intersection. A corner to my right and a split straight ahead. I can also hear movement nearby. Not a fight, but maybe a combatant.

“Marshall!” I shout as I step out to find a gun pointed right at me.

It’s a particularly large combatant. A mountain of a man dressed in black and moving like a malevolent shadow that fills the tight corridors.

The shadow nods, and moves on.

I follow.

As they round the next corner, gun first, darting with an unexpected burst of speed, they encounter a small group that immediately surrenders. Hands up.

It turns out that this faction is a group of girlfriends of some of the others. They don’t really want to be here, and they are finding it quite stressful. They have adopted a tactic of avoidance.

The large shadow does not fire. He accepts the surrender and waves them off.

He turns to me. I can’t see his face as it is completely hidden by a mask, but his voice has a hint of amusement.

“I don’t know why they are surrendering to me. They are on my team.”

And then he’s gone.

A siren wails. The first session is over.

Back in the barracks I meet up with my nephew. Like the others he is now unmasked and enjoying provisions of fizzy pop and handfuls of Haribo. The warehouse is riddled with the December cold and you can see everyone’s breath, yet many of them are drenched in sweat.

I ask the kid how it went and mentioned I hadn’t seen him during the entire session and I asked where he had been. He tells me he was over at the other side of the zone in an intense battle that I had somehow missed.

I figure that I’m going to follow him during the next skirmish, which will be objective based. One team will be defending a base whilst the other is tasked with infiltrating it.

We head back in, masked up, and guns reloaded.

I immediately lose him as the combatants take their starting positions, so I start to traverse the zone towards the objective.

That’s when I started getting shot.

The first couple were forgivable ricochets. Little ball bearings bouncing around corners.

The next time I was shot head on.

I was lining up a photograph of a small squad that were moving on the base. They were packed tightly in a narrow corridor and I aimed from a doorway off to one side. A member from the opposing team shot around the corner, and surprised by the tactically daft conga line of enemies, opened fire, spraying bearings as fast as they could, swinging the gas-powered gun in a large arc.

I took one to the chest, just below where I was holding my camera, causing me to lean back into the doorway to avoid any more.

Not exactly a war crime. It didn’t feel deliberate.

The rules state that he would still have to treat shooting a vested participant as if he had been shot, but it mattered little as they had also been pelted with shots from the opposing team.

As I neared the base, despite making my presence known, I would be repeatedly shot, and on one occasion I suspect deliberately so. There was clearly something greater at stake in this round, or perhaps the combatants were becoming hardened to the realities of combat, adopting a shoot first, question later policy of self preservation.

The base was defended successfully, repelling waves of attackers from multiple directions.

The siren wailed and we retreated back to the barracks once more.

I used the opportunity to take the last remaining shots on a roll and insert a fresh one under reasonable lighting conditions. Looking busy, I was able to eavesdrop on some of the chatter.

I expected tales of daring. Near misses. Brilliant action. Instead, most of the combatants talked about their civilian life. Of school, and work and families at Christmas. There also appeared to be a growing animosity between the two teams. It was hard to place, but felt like frustration.

After asking around I found out that the teams were a mix of regulars and casuals. A large group of first timers had turned up and were not especially happy at being shot so much.

Talking to one of the regulars, he explained that often people turn up having played an awful lot of video games and expected their experience to translate into a real world situation. The difference, he said, is that the regulars know to take it slowly and to treat this as a team sport. That one well placed shot is better than a hundred sprayed rounds.

As he says this, he looks at my camera, as I feed the new leader into the winding sprocket, and feel a slight twinge of embarrassment.

“Taken any good ones?”

I really don’t know.

The next session would be my final session.

This would be a “King of The Hill” game where both teams would try to occupy and hold a point in the zone.

A chess clock, on the ‘hill’, is used to keep check over which team holds the point the longest.

This would be the most chaotic battle of the day. The Hill itself was the ‘Fire Escape’ section of the zone. Of all the zones it was the most permeable and well lit. It also had a real fire escape, but we were briefed not to open that.

Safety first.

As the battle for the fire escape started, there was an uneasy sense of chaos. Several friendly fire incidents occurred immediately as two squads converged on the hill at the same time.

Suppressing fire was being used effectively to block off corridors.

I managed to get winged a few times too. Once in the middle of shouting the word “Marshal!”. The Geneva Convention be damned.

It seemed that no side got a grip on the hill. As soon as one side took it another moved in. Like a game of speed chess the clock was being punched every other minute.

I witnessed a brief period of maybe five minutes where a small squad managed to hold the area successfully, but had forgotten to press the timer.

I rattled through my film, trying to capture as many shoot outs and manoeuvres as I could. I felt that I was getting the hang of this. Seeing the battlefield through my viewfinder I had become a disembodied observer, floating about unbothered by the many face-level projectiles.

And then the siren.

The game was being cut short and no one seemed to know why.

My hi-vis vest had suddenly become a beacon of authority and the combatants were asking me what to do. Not having much idea I directed people back towards the barracks. It turned out to be the correct move.

As we approached the exit to the zone there were some raised voices. Angry voices.

There had been a war crime. A genuine Airsoft war crime.

I had missed it. I had failed to capture perhaps the most singular incident of this combat.

Talking to the troops later I discovered that one combatant had not only entered the other teams base, a designated safe zone, he had punched another player. This had all happened under the watch of a marshal.

And that was it. The game was ended.

In scenes reminiscent of Dr Strangelove’s, “Gentleman you can't fight in here, this is the War Room”, actual violence had been a transgression in the simulated warzone of Airsoft.

[I GOT SHOT FOR THIS]

[RULES]

At the time of writing over 166 journalists, including photographers, videographers and writers, have been killed in Palestine by Israeli forces.

The Geneva Convention makes it clear that these people are not legitimate military targets, however, evidence is emerging that many of these deaths were deliberate.

Thibaut Bruttin, the director general of Reporters Without Borders, states, “For 15 months, journalists in Gaza have been displaced, starved, defamed, threatened, injured and killed by the Israeli army.”

The IDF has responded with accusations that the reporters were actually militants in disguise, but have yet to provide any evidence to support the claim.

[BURDEN]

In an interview many years later, Chris Burden states that the idea for Shoot was this notion of the bullet just grazing his arm, leaving a single poetic drop of blood for the camera to capture.

“The bullet would whiz by my arm, and it would scratch it, and one drop of blood would roll down my forearm. That was the ideal-ideal.”

That wasn’t how it went. The flesh wound he was left with also punctured the boundary between performance and reality.

The idea of being shot against the reality of it.

The interesting thing happens because the camera was there. We saw what actually happened, not what was supposed to happen.

The two young men in the video had been watching the footage of the Vietnam war on their televisions, seeing young men wounded and shot on a nightly basis.

They were seeing what actually happened, not what was supposed to happen.

Bruce Dunlap, the shooter, was drafted but never saw action despite being trained as a marksman.

In a way, they were play acting. They were living out a childhood fantasy of being Cowboys. They were firing a gun and forging a path through a new frontier.

But, that act used a real gun and the performers were nothing other than what they were — and artist and a marksman.

What makes this piece exceptional was that it was recorded as an image.

That’s what made it real.

Guns and cameras, a shared language with a different purpose.

Guns are unreal. They unmake things.

Cameras make.