Episode 5: OBSOLETELY

[STRONG MAN]

Young Adam was a big fan of Geoff Capes, championship shot putter and renowned strong man.

Capes had won the inaugural Britain’s Strongest Man competition in ‘79. He’d go on to compete in The World’s Strongest Man competitions too, representing the UK. In 1983 following a closely fought contest with the self-proclaimed Icelandic Viking, Jón Páll Sigmarsson, Capes managed to come a close second.

Sigmarsson, eleven years younger than Capes, took the title proclaiming, "The King has lost his crown!".

Capes retorted, "I'll be back", a full year before another strongman, Arnold Schwarzenegger would make the phrase their own.

There is an alternative timeline where The Terminator crushes the skulls of humanity underfoot whilst sporting a grizzly black beard and speaking in a Lincolnshire accent.

It would be a while before young Adam would see The Terminator though, and when he did it was on a badly copied VHS, delivered in a white van.

Until then, he made do with watching Geoff Capes tip over cars on TV.

[NOSTALGIA]

This isn’t about nostalgia.

I don’t miss any of this, not really. It’s just the pool I learnt to swim in. An obsolete pool, but one I could see the edges of, one I knew where the deep end was.

This isn’t nostalgia, a sorrow for the home.

This isn’t nostalgia, there’s no comfort in it.

[BOX]

[YELLOW PAGES]

Legend has it that a printer in Wyoming ran out of white paper and started to use yellow to print their telephone directories at the end of the 19th century.

It feels apocryphal, especially considering how iconic the Yellow Pages became.

In the UK it started in Brighton.

The General Post Office ran a small classified section in the local telephone directory.

The pages were yellow.

By the time British Telecom bought it in 1984 there were 70 local editions covering the UK.

The Yellow Pages were delivered free of charge to most households. You’d find them stacked up near the phone alongside the local telephone directory.

There were, at its peak, 28 million copies in circulation in the UK. They were such a fixture of everyday life that you didn’t really notice them.

Our local edition in the 90s was nearly two inches thick. It was a solid yellow monolith. A catalogue of commerce.

Hairdressers, plumbers, taxi firms. This is where you’d find them.

They were somewhat essential.

In 1994, however, the internet arrived.

It would take 26 years to kill off the Yellow Pages, but the decline was noticeable. Each edition would get a little thinner until it felt more like a pamphlet.

In January 2019, 23 million copies of the last edition were sent to households in the UK.

Over the course of its life, the Yellow Pages had printed just shy of a trillion pages, a combined thickness capable of nearly three return trips to Mars.

[SKEUOMORPHISM]

A skeuomorph is an object that retains design cues from structures of its ancestors.

A good example is an electrical light fitting that mimics a candle.

Or the handset icon on your phone looking like that of a landline rotary phone and nothing like the glossy black rectangle in your hand.

It’s the bookshelf layout of your e-reader.

It’s the envelope icon on your email app or the trash bin when you delete them.

It’s the shutter sound on your phone’s camera.

It’s the 3.5” floppy disc of the save icon.

It’s film reels on streaming platforms, or the video tapes.

[STRONG MAN]

It was probably the vikings that started the notion of the strong man competition.

About a millennium ago, a chap called, “Orm Storolfsson the Strong” demonstrated his strength by walking three steps whilst carrying the mast of the longship, Ormen Lange.

The mast was reported to be eleven yards long and weighed around 650kg.

After three steps, his back broke.

Then there was Milo of Croton, from Greece.

He was reputed to be able to run for a mile with a fully grown Ox on his back.

Legend also tells that he saved the life of Pythagoras by holding up a collapsing temple roof.

On one occasion, however, he was demonstrating his strength by ripping a tree apart when he got stuck in it, and then died after being eaten by wolves.

Maximinus Thrax, of Rome, demonstrated his brute strength by crushing rocks in his hands. He didn’t die whilst doing this, but he did gain fame for once punching a mule out cold.

Which leads us to the modern era.

The highland games, where tossing the telegraph pole-like cabers is the fashion, gave way to televised contests.

Lifting cars, and increasingly heavy stones. The Farmers Walk… all good, slightly less hazardous feats of strength, safer for the strong man and safer for any by-standing mules… and the ultimate demonstration of strong man credentials, ripping a Yellow Pages in half with your bare hands.

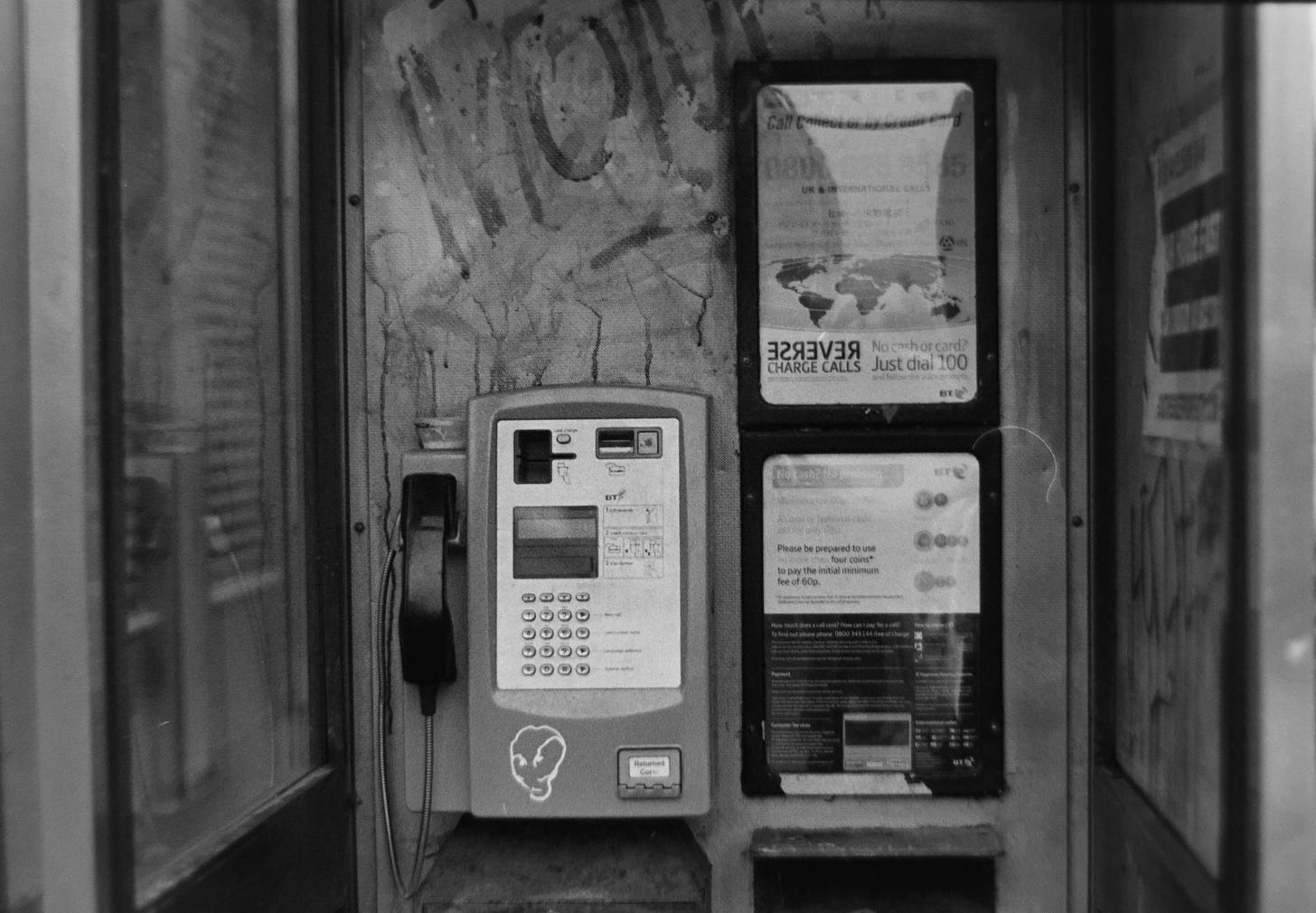

[PHONE BOXES]

Every phone box deserves a blue plaque.

They are not just sites of phone calls, they are sites of human stories. They are the locus of travel arrangements, nights out, love stories and late dinner arrangements.

They are calls home.

They are calls for help, and calls for thanks.

They are teenagers standing in the miserable cold, pushing ten pence pieces into a slot to keep themselves connected to their tenuous social life.

They are shelters, they are taxi hailing points.

But most importantly, they are totems, not unlike the legendary standing stones that litter the UK. They stand for something long ago lost to progress, but yet somehow resonant within us.

These rectangular, piss-smelling upright coffins are the burial mounds of the early information age.

Legend has it that even to this day you can lift the receiver and hear a sound that has transcended time. It is the note that starts all things, the primordial dialling tone.

[MODEMS]

We are almost always connected now, so much so that connecting to the internet feels like an arduous burden.

The absolute faff of having to find and enter a password to connect to Wi-Fi. It’s a wonder we get anything done at all.

Back then, however, we had dial-up.

For those of you young enough to have never experienced it, dial-up required you to have a box that attached to your landline phone socket.

When the time came to go on the internet you would prod it into screaming loudly down the wire until it summoned a connection.

That noise is still in the heads of old people as they walk around to this day. It’s like an ear worm that will forever mean ‘internet’.

What they were hearing was the ones and zeros being shunted a great distance incredibly swiftly. They heard the song of the machines and communed with them.

At least until someone wanted to make an actual phone call, in which case the link was broken and you’d probably have to start that download all over again.

You can still get onto the internet with dial-up. For some people this is the only way they can access our digital commune.

To give you some perspective, the current bbc.co.uk home page is 1.44Mb in size.

Using modern ADSL or 3G you can expect to wait between one and five seconds to see this page.

With a 56k dial-up modem, you’d be waiting close to seven minutes.

[INTERNET CAFES]

They still exist.

The internet cafe, or if you are feeling particularly authentic ‘the cybercafe’, was a 90s phenomenon.

A place where you could go and log on to the internet.

The big advantages were they often had faster connections than you could get at home, plus, many of us still didn’t even have computers back then.

It must have sounded like the best business idea in the world. Start a cafe, hook it up to the internet and enjoy a life of relative ease and custom.

Sure, you’d have to clean the keyboards and occasionally remove the rubber ball from the mouse in order to untangle the fluff, but otherwise, this would be the future.

I can’t remember the last time I was in one. I feel like it might have been the mid-2000s, and I think I was in London.

As I said, they do still exist. Mainly in less affluent areas, or areas with a highly transient population. There are some that found a sustained life as LAN party cafes, where you can congregate with a bunch of friends and shoot each other in a way that is less exhausting than laser-tag.

I bring this up, because much like phone boxes, these places were sites of connectivity. They were sites of communal connectivity. We all went somewhere to go somewhere else. Essentially these were the places where we transcended.

In these times of never-not online, the journey has been cut short and we’ve lost sight of our travelling companions.

We are at a destination without leaving anywhere.

That said, if you go to any cafe now, it is an internet cafe. Nearly everyone in there is connected.

[MEDIA]

Let’s go back to 1987.

It is dark outside, I think it must be in the Autumn. The news has just finished and a horn honks outside on the road.

The entire family gets up and heads out.

Parked against the curb is a large once-white van. A man is opening the side door.

A dim light inside illuminates the shelves.

Large book-sized VHS cases are crammed in.

Even then, as a child, I knew there was something dodgy about this, but that didn’t seem unusual, and besides, it made more sense than the bloke who came round once a week and asked us to predict the football scores.

This was the videoman.

When we talk about old media, and VHS in particular, people like to think back to the time of video stores like blockbusters. They like to remember these places that held banks of physical media, with the latest releases, and concession stands of sweets and popcorn.

But we didn’t have that. It would be nearly a decade before we had access to an actual Blockbuster, and the local video stores were still a 20 minute bus ride away.

What we had was far closer to the precursor of Netflix. We had media delivered to our door.

It was, of course, pirated media of dubious quality and provenance.

It felt exciting though, a van crammed with photocopied cover cases for films we hadn’t heard of. Sometimes there would be a description, but often it was just a title. Cases in the children’s section did not necessarily mean the contents were suitable for children.

I remember one copy of Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory that had been played so often that it was like watching it through a blizzard. That was how we spent New Year’s Eve in 1988. Sat around a small screen watching Gene Wilder test the mettle of children through a gushing storm of static.

I realise my education in film came out of that unwashed van. The lack of space meant that a form of curation had taken place. Partly, it was popularity that defined the stock, but I think the videoman had his own agenda. The selection of 80s horror was exquisite, and freely available to anyone with a pound coin to borrow it for a week.

Without this public service, I doubt that many of us would have been able to engage in pop culture in quite the same way. It fostered a communal conversation.

If anything though, it was a feat of strength. A single man carrying the entire weight of modern media onto our estate.

[HARD COPY]

2022 saw a 20% increase in vinyl sales from the previous year, totaling around $1.2 billion.

The year also saw a jump in cassette sales to over 343,000, nearly twice as many as the year before.

Also in 2022 revenues for CD sales increased by 21%.

Blu-ray is making a comeback. YouTube channels have discovered minidisc.

It’s not always pure nostalgia. Sometimes things were better.

And in what ways are these formats better than their modern counterparts?

In the main, it is about physicality.

Part of the argument suggests that cover art and being able to maintain a physical collection are two drivers of the resurgence.

Collectors of media are also curators. They not only curate their library but the space in which they hold their library. It is rather satisfying to arrange your collection by genre, artist or even colour.

Much in the same way that physical book sales seemingly increased when e-readers were launched, despite predictions to the contrary, it turns out that people who like music also like the physical media it is delivered on.

A growing consensus also considers the right to ownership.

Streaming services such as Netflix and Amazon’s Prime, act as rental services rather than sales fronts. Your subscription only covers you for the content they have. As other services set up, for example Disney+ and HBO, that library becomes fractured as competition demands they withdraw their titles from their competitor’s shelves.

The result is that any film or TV show you are watching can disappear at any point.

These business practices have also led to titles disappearing altogether as legal battles occur over who has the right to host the media.

One day your favourite film might just vanish in a way that seems unlikely if you own a hard copy in your home.

Another reason, given less room in the discussion, concerns volume. Your own personal collection of music sits on your shelf. Or maybe several shelves if you are a serious collector. Still, it is a finite space. Going and choosing something to put on is a limited expedition.

Even so, it can be hard to choose.

With online services, the landscape is vast. Finding something to watch or listen to becomes the purpose of these services, rather than the films or music themselves. Evenings can be obliterated by scrolling endlessly through whatever the algorithm offers.

There’s a certain type of frustration too, when you search through one genre after another only to find the same titles appearing in each one.

The illusion of choice becomes apparent.

[TEXTING]

I love you.

This isn’t about nostalgia. It isn’t about how things were harder, and that we overcame those hardships that defined us.

It isn’t.

What came next was harder.

444, 0, 555, 666, 888, 33, 0, 999, 666, 88

I love you.

No keyboard, just ten digits that you had to hammer repeatedly to get the right character.

Conversations poetically framed in 160 characters. Relationships maintained through fast tempo taps.

[DECORATION]

We are sitting in a trendy pub that describes itself as a micro-brewery. I think that is modern speak for “share tables with strangers”.

Despite the lack of space, the place is heavy on decoration.

All around us we are surrounded by corpses.

On a rail above us are the shells of old cameras. The fossilised husks of former picture boxes, each staring out through a cold, dead lens of an eye.

In the window a series of decommissioned typewriters cast shadows into the room. I suspect that, with a little care, they would still work. Typewriters, the mechanical ones, are particularly resistant to time. A little sewing machine oil, a new drawstring and a recently inked ribbon is usually all that is needed.

There’s an old rotary phone on the edge of the bar.

This feels like a hunting lodge of technology.

This isn’t nostalgia, this is a form of skeuomorphism.

There’s a complex lesson in semiotics here.

This is all set design… but what is the message?

It might seem like nostalgia, but many of the patrons have never encountered a working typewriter. These are totems. They are tiny little shrines to a prayer of tactility and limitation. They are signals of purpose.

Each one represents a form of communication, a form of telling stories and connecting with people. These objects are here to highlight the purpose of a bar. You are not here to sit alone and drink alcohol, you are here to make new stories and share old ones.

Or maybe they are memento mori. A reminder of how the old ways die, if not in body, but in purpose. That all machines, including humans, become obsolete, and that means we should celebrate them whilst they are alive.

Everyone here is a survivor of the past.

We surround ourselves with these objects as a reminder of that fact. They represent not the comforts, but the troubles that we overcame. They are the stuck characters, the calls in the cold. The slow, error-prone inconveniences of our lives.

I think this is the reason the phone boxes still litter our streets. They are a reminder that we choose to be connected, no matter how much it feels like the default.

Against one wall is a bookcase. It contains the usual filler of ageing hardbacks bought as a job lot. They are not for reading, they are for decoration.

There is a section of National Geographic magazines too, probably saved from a fate of dentists waiting room fodder.

Except, in amongst the thin yellow spines is one that sticks out. It doesn’t belong there. It’s a little thicker. It’s a little yellower.

It looks as if anyone in here could stand up, march over and grab it. Twisting it between their hands until they rip it clean in half.

It’s a 2019 edition of the Yellow Pages.